Pocket hole joinery is popular among woodworkers these days.

Personally, I prefer traditional joinery, figuring it's much better.

But I wanted to know how much better. So I bought a

Kreg pocket hole jig, even though I swore I'd never buy one.

Pocket hole joinery is popular among woodworkers these days.

Personally, I prefer traditional joinery, figuring it's much better.

But I wanted to know how much better. So I bought a

Kreg pocket hole jig, even though I swore I'd never buy one.

Pocket hole joinery is popular among woodworkers these days.

Personally, I prefer traditional joinery, figuring it's much better.

But I wanted to know how much better. So I bought a

Kreg pocket hole jig, even though I swore I'd never buy one.

Pocket hole joinery is popular among woodworkers these days.

Personally, I prefer traditional joinery, figuring it's much better.

But I wanted to know how much better. So I bought a

Kreg pocket hole jig, even though I swore I'd never buy one.

I had a whole lot of scraps, 17 mm x 59 mm, probably spruce, and of consistent density, so I used that for my tests.

The nice thing about pocket hole joints is that they require almost

no set-up.

The nice thing about pocket hole joints is that they require almost

no set-up.

You can buy fancier jigs which integrate the pocket hole jig and clamping, but clamping the really basic jig and workpiece in a vise worked out really well. If I used pocket holes much, I think I'd make something to attach the jig to the front jaw of the vise.

I never see people using glue with pocket holes when I watch YouTube videos, so to make it representative, the pocket hole joint doesn't have glue in it.

The joint I made with the pocket hole was a configuration that would traditionally

be accomplished with mortise and tenons.

The joint I made with the pocket hole was a configuration that would traditionally

be accomplished with mortise and tenons.

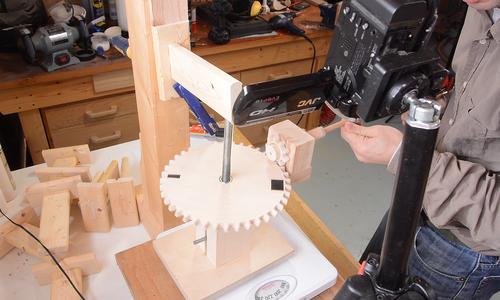

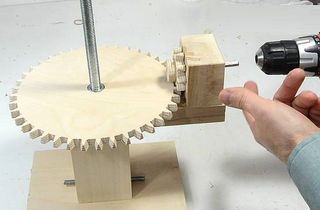

I mounted the test piece in my test apparatus with my new screw jack, on a bathroom scale. I marked 15 cm from the joint for where to apply the force. A video camera is aimed at the scale to record the force.

I made four pocket hole joints to break. At about 50 pounds applied 15 cm from the joint,

the joints started to visibly open up a gap, but the ultimate breaking force was

about twice as much.

I made four pocket hole joints to break. At about 50 pounds applied 15 cm from the joint,

the joints started to visibly open up a gap, but the ultimate breaking force was

about twice as much.

My four joints completely failed at 95, 120, 75, and 105 pounds

Average: 99 pounds

1 pound of force is 4.44 Newtons.

Making the test joints

Next I tried some dowel joints. I made these using my

self-centering dowel jig and glued them with Titebond 3.

Next I tried some dowel joints. I made these using my

self-centering dowel jig and glued them with Titebond 3.

The dowel joints did not visibly deform until the point of failure, which was usually accompanied by a "pop".

The breaking forces of the dowels joints were 160, 160 and 149 pounds.

Average: 156 pounds.

Next I tested some mortise and tenon joints. I wasn't sure which glue to use, so

I made a total of nine joints, three glued

with yellow (LePage) carpenter's glue, three with Titebond 3, and three with epoxy.

Next I tested some mortise and tenon joints. I wasn't sure which glue to use, so

I made a total of nine joints, three glued

with yellow (LePage) carpenter's glue, three with Titebond 3, and three with epoxy.

Mortise and tenon joints are normally more work to make than dowel or pocket hole joints. But once I had my pantorouter and my slot mortiser set up to cut them, these actually were the fastest joints to make. They are also the cheapest to make if you don't factor in equipment cost.

Failure of the mortise and tenon joints was very spontaneous, with a large pop. There

was no visible deformation before failure.

Failure of the mortise and tenon joints was very spontaneous, with a large pop. There

was no visible deformation before failure.

The breaking forces were:

Mortise and tenon with yellow glue: 235, 235 and 195

Average: 222 pounds

Mortise and tenon with Titebond 3: 190, 180 and 235

Average: 202 pounds

Mortise and tenon with epoxy: 270, 225 and 215

Average: 236 pounds

As I expected, the traditional joints were stronger than pocket hole joints.

Mortise and tenons were twice as strong as pocket holes.

That said, half as strong as a mortise and tenon joint is actually pretty good

for something quick and dirty.

As I expected, the traditional joints were stronger than pocket hole joints.

Mortise and tenons were twice as strong as pocket holes.

That said, half as strong as a mortise and tenon joint is actually pretty good

for something quick and dirty.

But the troubling thing about the pocket hole joints is that they open up partially at much lower forces. If you make furniture using pocket holes, I'd recommend not filling in the pockets so that you can re-tighten the screws if necessary.

The dowel joints were 1.5x stronger than the pocket hole joints. I could have made the dowel joints stronger by using four dowels instead of two. Earlier tests indicate that such a joint should be nearly as strong as a mortise and tenon joint.

| Joint type | Breaking forces | Average | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pocket hole | 95, 120, 75, 105 | 99 pounds

| Dowel | 160, 160, 149 | 153 pounds

| Mortise and tenon with | LePage carpenter's glue 235, 235, 195 | 222 pounds

| Mortise and tenon | with Titebond 3 190, 180, 235 | 202 pounds

| Mortise and tenon | with 5-minute epoxy 270,225,215 | 236 pounds

| |

The epoxy did best of all this time. In my earlier test epoxy had done very poorly. At the time, I didn't know that epoxy goes bad over time, and my epoxy glue was probably expired. I buy a gallon of yellow glue every 2-3 years and have never run into problems with it getting too old though.

I actually feel better about pocket hole joints now than I did before. I guess they are a good match for rough palette wood projects, but I still don't think they are suitable for anything that could be classified as living room quality furniture.

A lot of people commented that my pocket hole tests were not valid

because I hadn't glued the pocket hole joints. Personally, I didn't think it

mattered that much, but to address the concerns, I decided to redo the pocket

hole tests, with glue this time.

A lot of people commented that my pocket hole tests were not valid

because I hadn't glued the pocket hole joints. Personally, I didn't think it

mattered that much, but to address the concerns, I decided to redo the pocket

hole tests, with glue this time.

I previously made sure all my workpieces were the same density. To be consistent, I needed to use the same kind of wood, and I already used up all the similar wood in my previous tests. I already threw the scraps in with the firewood in my big garage workshop, so I had to go back and get what I hadn't burned yet. I then used the other ends of my samples to make pocket hole joints, and cut shorter pieces out of some other parts to have wood to screw against.

And then I waited two days to make sure the glue was definitely dry.

The reason I didn't expect glue to make much difference is that screw joints, including

pocket hole joints, always yield a bit before reaching maximum strength, whereas

glue joints do not yield, but pop open suddenly. so I expected the "butt joint"

part of the joint to fail before the pocket hole screws reached their maximum force.

The reason I didn't expect glue to make much difference is that screw joints, including

pocket hole joints, always yield a bit before reaching maximum strength, whereas

glue joints do not yield, but pop open suddenly. so I expected the "butt joint"

part of the joint to fail before the pocket hole screws reached their maximum force.

And sure enough, every joint I tested cracked open before reaching maximum force. I doubt the failed glue joint contributed much to the ultimate strength.

The failure loads of the pocket hole joints were 115, 130, 115, 75 and 120 pounds, averaging 111 pounds.

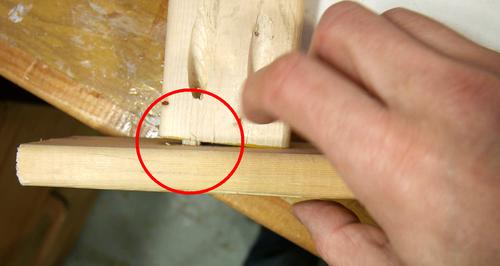

Interestingly, this time, most of the joints failed with the screw head breaking out of

it's pocket hole on the horizontal piece, whereas last time, all the joints failed

with the threads pulling out of the vertical piece.

Interestingly, this time, most of the joints failed with the screw head breaking out of

it's pocket hole on the horizontal piece, whereas last time, all the joints failed

with the threads pulling out of the vertical piece.

I'm pretty confident this was caused by me having set up the jig slightly differently this time, drilling slightly deeper. This became evident by the fact that on most joints the tips of the screws protrude out the other side of the wood, but not last time. But, if anything, for these joints, drilling deeper increased the strength.

I also had used some slightly lighter wood to make a couple of pocket

hole joints the day I published the video. Weighing the wood,

it was only 8% less dense than my other samples. When I made these

joints, I still had the jig still set the same

way I had for my previous tests. I'd previously rejected these slightly

lighter boards because they might bias the tests. Both of these joints

failed at just 75 pounds. At left, you can see the screw penetration

of these joints.

I also had used some slightly lighter wood to make a couple of pocket

hole joints the day I published the video. Weighing the wood,

it was only 8% less dense than my other samples. When I made these

joints, I still had the jig still set the same

way I had for my previous tests. I'd previously rejected these slightly

lighter boards because they might bias the tests. Both of these joints

failed at just 75 pounds. At left, you can see the screw penetration

of these joints.

Of the samples with the same wood as my previous tests, the one that failed at just 75 pounds also had the screws protruding the least. I had readjusted the jig after seeing the screws come out the back on the other ones I assembled. I think the most important factor affecting the tests here is how deep the screw goes into the vertical piece.

I also made some butt joints (no screws) to see how much the butt joint itself could contribute to the strength. These failed at 35, 50 and 40 pounds. The butt joints all failed with a pop, without yielding any before failure. And again, given that the glue was already cracked open by the time the pocket hole joints reached maximum strength, I just don't see the glue contributing to the ultimate breaking force.

And, what conclusion do I draw from this?

Of course, given reaction to my previous tests, I am also equally convinced that there are plenty who will refuse to believe that. It's like a form of religion, and people hang on to their beliefs dearly, evidence notwithstanding.

And if you don't want to believe me, instead of arguing with my methodology, why not run some tests of your own? You could use a bottle jack or a scissor jack instead of my fancy screw jack. Beyond that, you just need some wood, a video camera, and a bathroom scale.

Screw jack for my joint tester (2015)

Screw jack for my joint tester (2015) Testing different glues (2009)

Testing different glues (2009) Dovetail vs. box joint (2010)

Dovetail vs. box joint (2010)